Christine Egan Physical Therapy

Christine’s Pediatric Physical Therapy Blog

Jack Lawson: Embracing a New Perspective

Jack, 26 (at left) hiking with his brother Theo, 28

Before applying to Harvard Business School, Jack Lawson never seriously considered Cerebral Palsy’s influence on his life. Growing up, Jack said he wanted nothing more than to fit in with the rest of his peers. He distanced himself from the condition as much as possible, hoping others would notice him for anything besides his physcial challenges. But something about the busniess school application process was a revelation for him.

“I think I’ve finally internalized that I’m not ‘normal,’ and that’s okay,” Jack said in a speech given to his section at Harvard Business School.

Jack remarked that the sentiment to “beat” Cerebral Palsy was embedded so early in his life that he doubts he will ever lose that motivation. But he embraces his condition today in a way he never would have as an adolescent.

“I actually told my parents recently that if I had to do it all over again and had the choice, I would choose Cerebral Palsy,” Jack said.

His mother, Jackie Lawson, insists she knew something was different about Jack the day he was born. Call it maternal intuition, but sure enough Jack was diagnosed with left hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy at nine months old. Immediately following that, Jackie set up Physical and Occupational Therapy sessions five days a week. Jack began seeing Christine Egan MPH, PT C/NDT at the age of two and a half, when he began a TES (Therapeutic Electrical Stimulation) Program, founded by Karen Pape, MD. The earliest sessions Jack can remember were in Kindergarten with Christine, where he began working on balancing and strengthening exercises for the left side of his body.

“You don’t necessarily see progress in the day to day,” Jack said, “but over the long run therapy helps.”

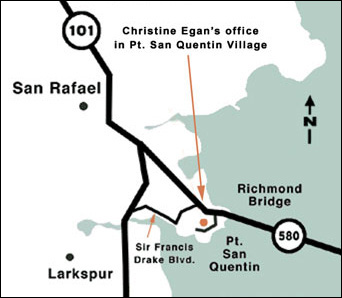

Once he connected the therapy to his improving strength and dexterity, Jack attacked the exercises with newfound vigor. He still recalls the “No Whining” sign displayed in Christine’s office as the mantra of his training. Jackie was just as committed, driving many hours back and forth to Christine’s San Rafael office from their Dublin, California home.

“My parents really put [the kids] first — I think especially me with this stuff,” Jack said. “Not to say I took it for granted when I was younger but I don’t think I realized all the time they gave and the sacrifices they made. I really appreciate that now.”

Jack improved physically to the point of playing youth sports, like basketball, baseball and soccer. “I was still a pretty active kid,” he said. “I would be out on the soccer field in a full cast.” But he was still a step behind other players. Rather than wallowing in self-pity, Jack realized he could outsmart his opponents rather than overpower them. For instance, Jack played a smarter defense during soccer games, anticipating the route of oncoming attackers and cutting them off before they had a chance to outrun him.

“I realized my physical capabilities were limited,” Jack said. “I had to compensate with my mind where I was incapable with my body.”

Despite his immense progress, Jack was still dissatisfied. “I aspired to be someone who effectively ‘beat’ Cerebral Palsy. Here I was, working my hardest to improve my condition, but I was never satisfied with the results,” Jack said. “People could still see my limp. I still had a hard time finishing tests on time because I wrote so slow. I had to practice dressing in and out of my PE clothes so I wouldn’t be late to gym class in middle school. Buttoning my right cuff on a dress shirt? Forget about it.”

Jack remembers his expectations shifted when he attended a high school football game knowing the opposing team’s backup quarterback had Cerebral Palsy. “See, you can do it too,” Jack thought to himself. But Jack’s image of a conqueror of this condition was shattered when the quarterback played only one set of downs at the end of a blowout game. This was his wake-up call that he viewed his condition in the wrong way. “What I aspired to be…someone who effectively ‘beat’ Cerebral Palsy, didn’t really exist.”

Now at the age of 26, Jack speaks of his condition with candor and humor. He appreciates the work ethic his early physical training instilled in him. He recognizes how Cerebral Palsy has taught him to think “outside the box.” He is thankful his family had the resources to assist his growth. Jack once saw his Cerebral Palsy as an adversary, but today he recognizes the condition as just another part of his identity.

“I spent basically my whole life running from any association with this condition that has defined me more than perhaps anything else,” Jack said, concluding his Harvard speech. “On the contrary, this condition has given me one hell of a life.”